Researchers working in the South China Sea were astonished to discover two marine vessels that once served the fabled Ming Dynasty.

Archaeologists hope the vessels can provide valuable insight into the marine capabilities of one of China’s most prosperous ancient dynasties.

China’s Ming Dynasty

Of all the powerful dynasties that ruled over China during the late medieval era, none have garnered attention from scholars quite like that of the Ming Dynasty.

From 1368 to 1644, this powerful dynasty brought forth a period of stability for China. Known for their impressive trading capabilities and preservation of culture, the rulers extended Chinese influence well beyond their borders.

Archaeologists Begin Long-Term Work

The surprising discovery was made last October after research teams had been searching the sea floor for items of interest.

According to an announcement from the Chinese government, archaeologists will begin to excavate the site using deep-sea equipment in a process that could take up to a year.

Artifacts Found 1,500 Meters Below Sea Level

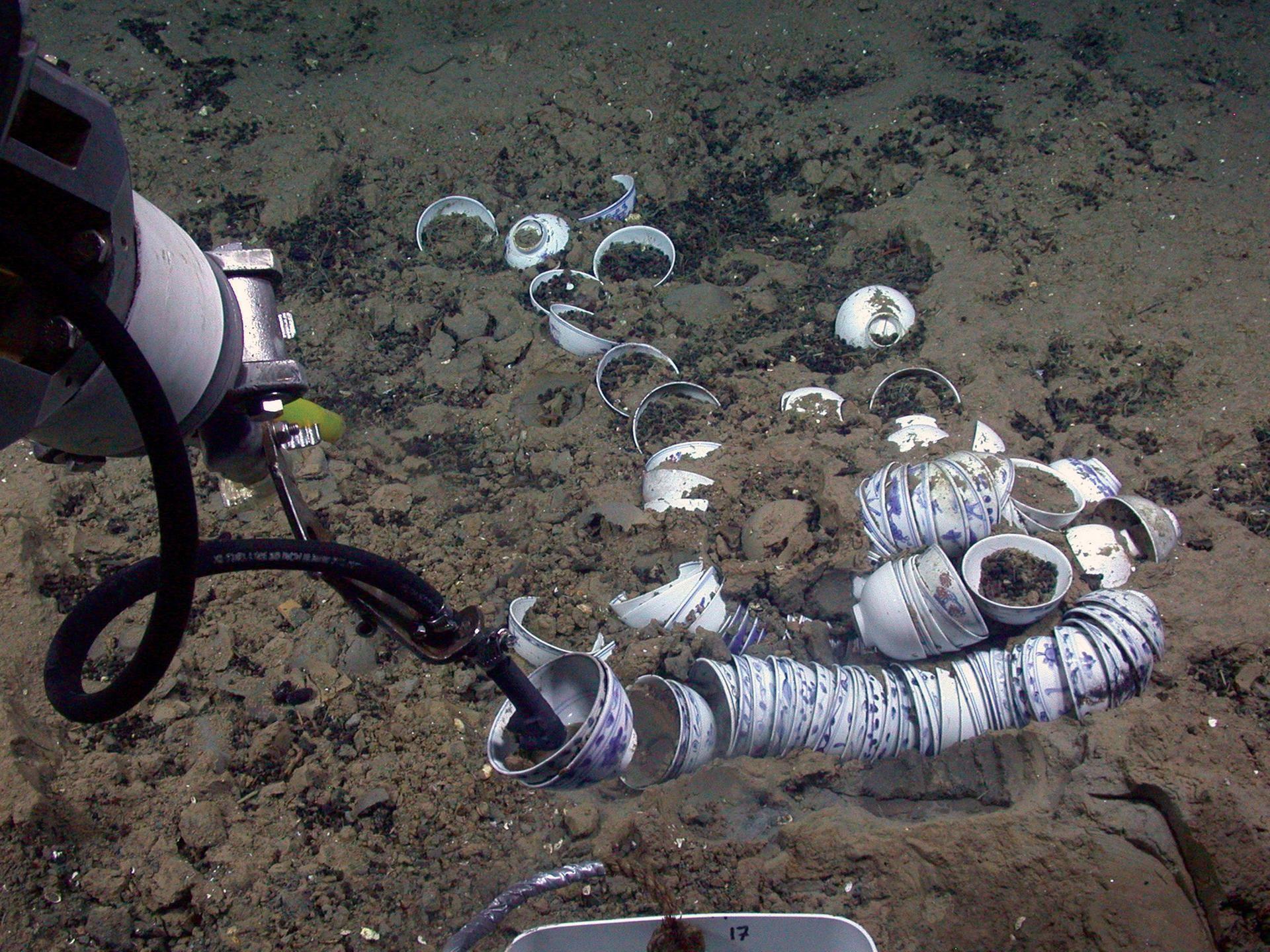

The team behind the discovery revealed the ships sit at an impressive depth of 1,500 meters below the surface of the South China Sea.

While deemed a lucky find, it appears fortune was on the researcher’s side as the ships are “relatively well preserved, with a large number of cultural relics,” according to what one spokesperson told The Guardian.

Relics of the Silk Road Era

After initial inspections, the team of researchers announced the ships contained Ming-era artifacts, including stacked timber and porcelain goods.

Chinese archaeologists are hopeful the discoveries can further their understanding of the Ming dynasty’s Silk Road trading routes.

Historical Significance and Cultural Value

One archaeologist involved with the excavation work, Yan Yain, says the discovery is of heightened importance in trying to understand ancient China’s overseas trading networks.

“The well-preserved relics are of high historical, scientific, and artistic value … and is a major breakthrough study for the history of Chinese overseas trade, navigation, and porcelain,” he said, per The Vintage News.

Early Dating of the Wrecks

Initial dating methods have provided researchers with information suggesting that one vessel dates to the Hongzhi period, taking place from 1488 to 1505.

Meanwhile, the other dates to the Ming dynasty’s Zhengde period, which lasted from 1506 until 1526.

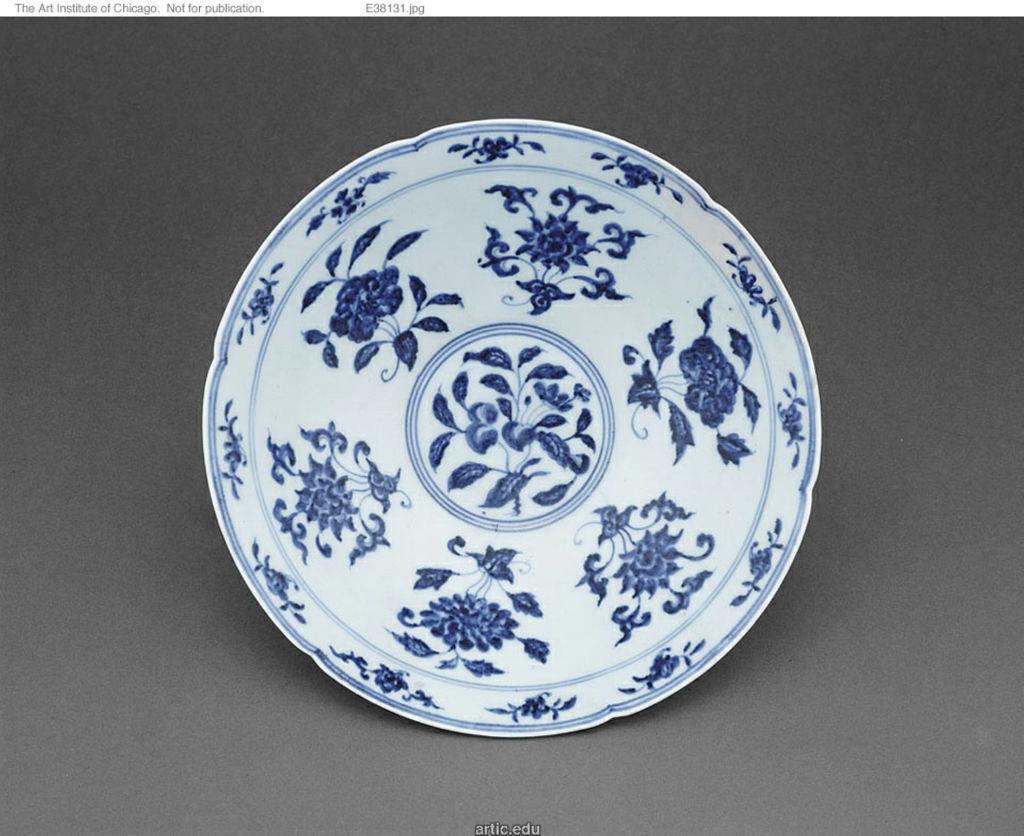

Extensive Porcelain Trading

The ship, dated to the Zhengde period, was packed with artifacts. According to best estimates, over 100,000 items made from porcelain remain on the bottom of the sunken vessel.

These items came in the form of jars, plates, and bowls, all of which were intricately decorated with Ming-era artwork.

Traveling on Important Trade Routes

The individual ships appear to have been traveling in opposite directions during their voyages, yet they were found less than 12 miles apart.

According to archaeologists, the location of the find indicates that both ships had been traveling along a vital trade route when they sank beneath the South China Sea.

Studying The Silk Road Martine Routes

Researchers have begun theorizing what role this maritime highway could have played for Chinese merchants of the era.

According to Tani Wei, director of the Chinese National Center for Archaeology, “It helps us study the maritime Silk Road’s reciprocal flow.”

Exploring the Depths of the Ocean

Thanks to the National Center for Archaeology and the Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, China has made great leaps in underwater archaeology in recent years.

Their laboratory makes use of the impressive Shenhai Yongshi, a submersible vessel that carries researchers to a depth of up to 5,000 meters.

Archaeologists Planning Ahead

According to archaeologists working on the project, over 50 dives are set to be carried out by April.

“We first need to figure out the condition of the shipwrecks, and then we can draft plans for archaeological excavation and conservation,” Song Jianzhong, a researcher at the National Centre for Archaeology, told The Guardian.