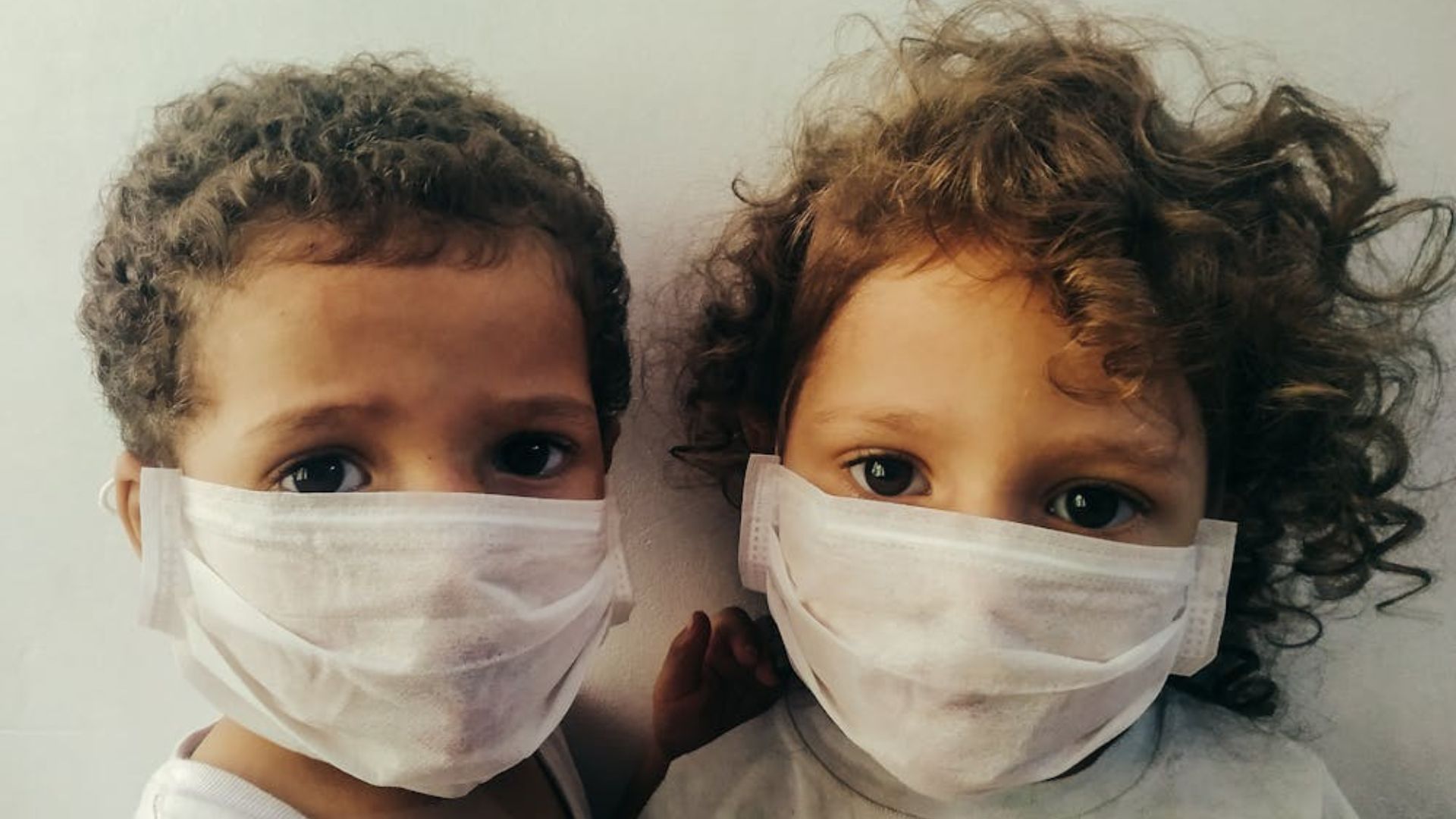

It’s been over four years since the world quickly ground to a halt following the outbreak of the Coronavirus in the United States -with schools, nurseries and most places of work closing and operating remotely.

Now, babies and toddlers of the pandemic years have reached school age, and new reporting reveals the full extent of the developmental delays they suffered as a result of pandemic-era restrictions.

Basic Skills Lacking

New York Times’ reporters Claire Cain Miller and Sarah Mervosh spoke to over two dozen childhood experts, teachers and pediatricians to gain unique insight into the lingering effects of the pandemic.

They found a generation of children were less likely to have skills expected for children of their age – such as emotional self-regulation, basic motor skills and the ability to problem solve.

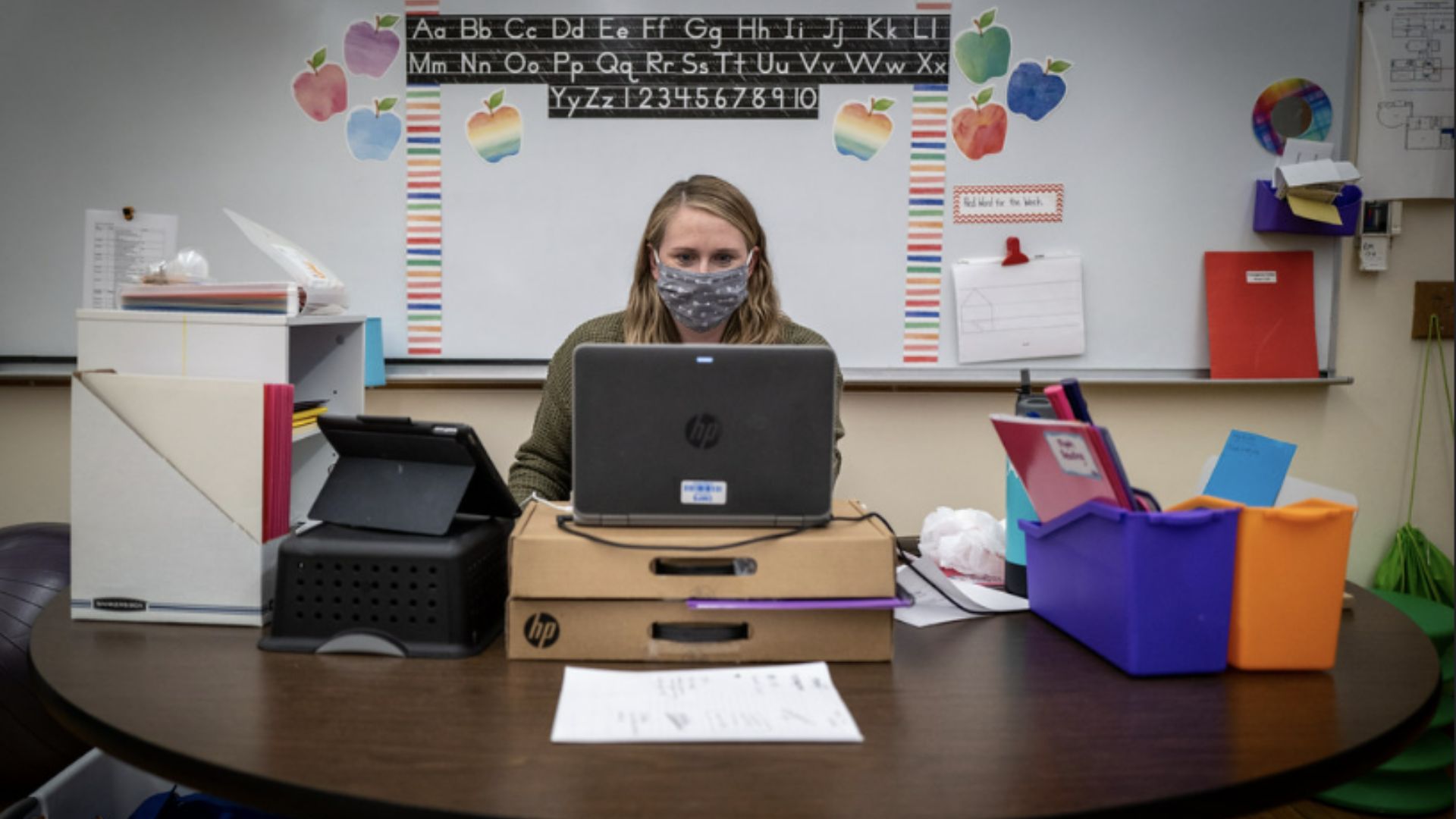

Teachers’ Voice Concern

Dr Jaime Peterson, an Oregon paediatrician and researcher, said, “I definitely think children born [during lockdown] have had developmental challenges compared to prior years,”

Peterson added, “We asked them to wear masks, not see adults, not play with kids. We really severed those interactions, and you don’t get that time back for kids.”

What Skills Have Been Lost

Brook Allen, a Tennessee kindergarten teacher, said that for the first time in her career, she was seeing students who could barely speak, couldn’t hold pencils, and weren’t toilet trained.

The Times reported that a Tennessee pre-K teacher, Michaela Frederick, “had to replace small building materials in her classroom with big soft blocks because students’ fine motor skills weren’t developed enough to manipulate them.”

Low Attendance Persists

Following months of remote schooling in 2020, many teachers have struggled to get kids to come back to class regularly. One teacher, Analilia Sanchez said she had “never had such a small class”.

Sanchez, who typically has class sizes of 16 and above, says she had just nine children in her class last year. She added, “I think [parents] got used to having them at home — that fear of being around the other kids, the germs.”

Screen Time Spike

Research shows that screen time for young children spiked during the pandemic, and has failed to return to pre-pandemic levels since the end of lockdowns.

This is concerning because excess screen time has been linked to shortening attention spans, poor motor skills, and other symptoms of developmental delays

“A Pandemic Tsunami”

Joel Ryan, who works with a network of preschools in Washington State, says America’s youngest children represent “a pandemic tsunami” that is about to hit the education system.

Kristen Huff, vice president for assessment and research at Curriculum Associates, added that “most, if not all, young students were impacted academically to some degree,” by lockdowns.

Stark Demographic Divides

The impact of the pandemic is less severe on some groups than others, suggests data from Curriculum Associates school testing results.

Children from lower incomes, and schools with higher numbers of Black and Hispanic pupils, have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic fallout. Meanwhile, pupils from higher-income households are generally keeping course with historical trends.

Emotional Dysregulation

Florida teacher Lissa O’Rourke said that since schools went back to in-person teaching, she’s noticed an uptick in pupils’ unable to regulate their emotions.

“It was knocking over chairs, it was throwing things, it was hitting their peers, hitting their teachers,” she said.

Reasons For Ongoing Struggle

Some experts suggest that increased parental stress during the pandemic had an adverse impact on children. Others think that decreased opportunities for children to interact with their peers during their primary socialization years were hugely detrimental.

However, experts believe it is still possible to make up for lost time. Clinical psychologist Catherine Monk said, “We 100 percent have the tools to help kids and families recover.” It’s just a question of whether leaders are willing to devote resources to doing so.