When British settlers first arrived in Canada on behalf of the Crown, they worked out a deal with Indigenous groups to obtain vast swaths of land. But there was a catch that is now coming back to haunt them.

Litigation brought against the government of Canada could result in a multibillion-dollar payday for the Indigenous inhabitants if the nation is forced to uphold a promise they made nearly two centuries ago.

Arrival of the Crown in Canada

Over 170 years ago, the British Crown worked out a deal with the native inhabitants of Canada to obtain vast portions of land in Northern Ontario.

Two treaties were signed in which the Anishinaabe tribe agreed to “fully, freely, and voluntarily” give their land to the Crown. However, they were allowed to continue fishing and hunting on the land, and Queen Victoria’s government would pay them an annual fee.

Making a Deal with the Indigenous Groups

After the Crown promised to share a portion of the wealth produced from the lands north of Lake Huron and Lake Superior, the Indigenous groups happily agreed to sign it over, hoping to gain generational wealth from the deal.

The payment started out small. However, the treaty contained a clause that allowed for an increase in the future if the land became increasingly prosperous.

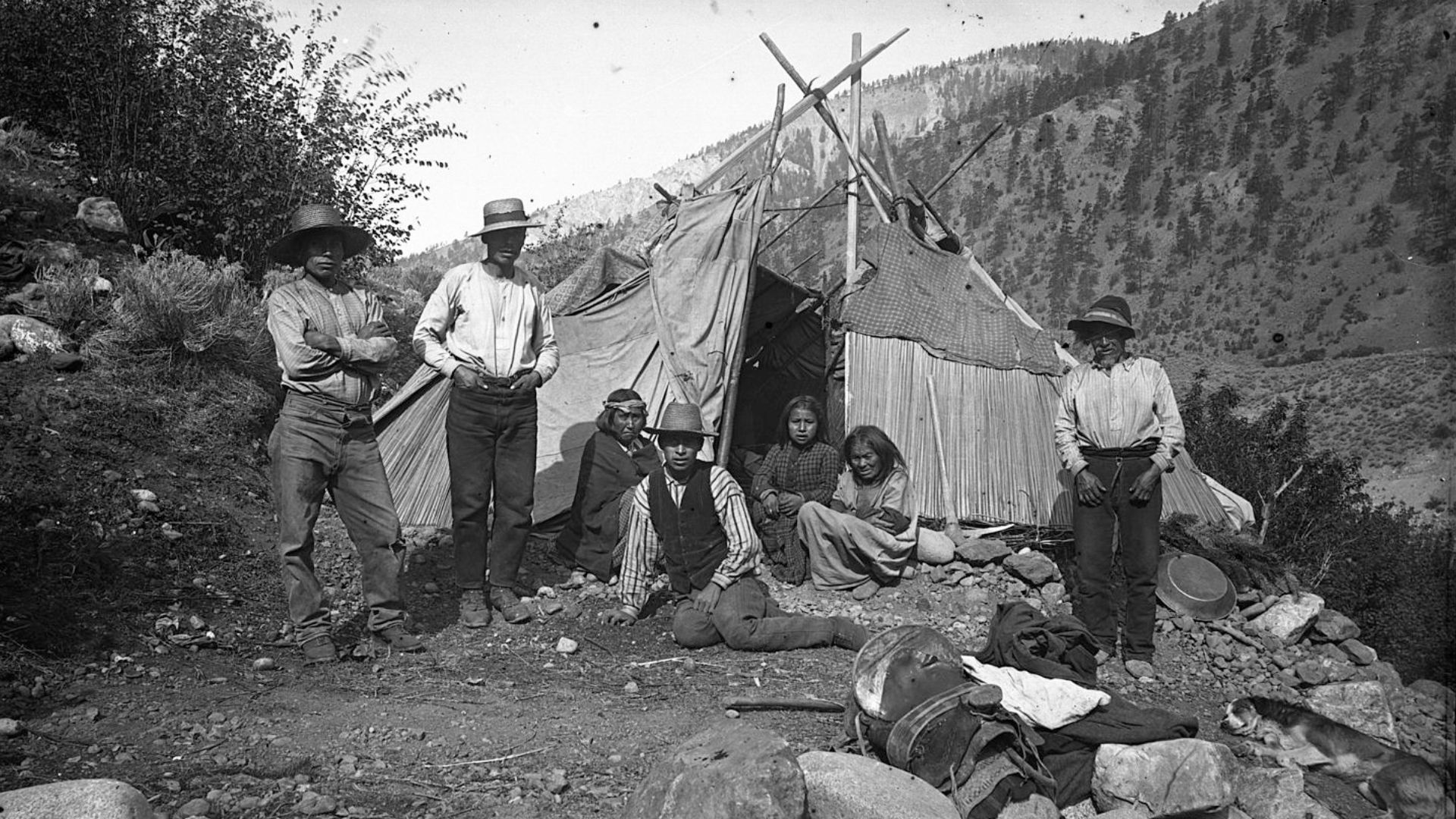

Indigenous Groups Battle Poverty

In the two centuries that followed, the Indigenous groups have since regretted their decision after receiving little to no compensation from the Crown.

Instead, as the Indigenous peoples continued to battle against poverty and other misfortunes, those associated with the Crown prospered greatly from trading the resources of the region.

First Nations Chief Speaks on False Promise

Tangie, who currently sits as the chief of Michipicoten First Nation, shared his thoughts on the false promise, claiming that only the Crown benefited from the deal.

“One treaty partner is getting rich at the expense of the other,” he told The Washington Post.

Consistent Disappointment from the Crown

Currently, the Michipicoten First Nation is situated just under 150 miles north of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Tangie claims his people have long awaited their fair share from the deal, yet it’s never arrived.

“Our elders have always said that the only consistent thing about the treaty is that it has never been honored by our treaty partner,” he said.

Broken Promise at Center of Ligtation Case

Now, it appears the groups of the region could be set for a mega payday as they continue to fight in court in hopes of ensuring the original treaty is upheld.

The legal case could result in the largest payout in the history of the nation. But it could also help dictate how the revenue from resources is spread among native groups in the future.

Bridging Generational Divides Through Legal Recourse

Brian Gover, a lawyer representing seven of the nations in the treaty litigation, highlights the necessity of legal intervention for First Nations.

He said to The Guardian, “Where do First Nations turn if they aren’t being treated fairly by government? They have to have recourse to the courts.”

Raymond Goodchild Testifies against Crown

A century after the original treaty, Raymond Goodchild testified on behalf of the Indigenous groups, claiming that the Crown did not honor its original promise.

Raymond went on to argue this left many Indigenous groups in poverty. During the 1990s, his testimony was used in a legal dispute that discussed the true extent of the broken promise and how much compensation the groups were entitled to.

The Stark Contrast of Living Conditions in Terrace Bay and Pays Plat

Goodchild’s upbringing in Pays Plat First Nation starkly contrasted with the neighboring town of Terrace Bay.

While Terrace Bay thrived with industries and modern amenities in the 1960s, Pays Plat was characterized by basic tar-paper shacks lacking electricity and running water. Goodchild recalls to The Guardian, that getting a home with running water took two decades.

Goodchild: A Symbol of Resilience

Goodchild, now 67, reflects the resilience of the First Nations. He said to The Guardian, “When I had my daughter, I said a prayer: ‘Let me give her a better life.’”

Despite living in poverty for most of his life, he has seen gradual improvements in his community, such as the introduction of running water and electricity.

The Continuing Struggle for Educational Equality

The Guardian reports that educational disparities remain a significant challenge for First Nations communities.

Between 2011 and 2016, Canada’s auditor general found that only 24% of students on reserves completed high school within four years, a stark contrast to nearby towns.

The Erosion of Rights and Cultural Heritage

Marcus Hardy, chief of the Red Rock First Nation, emphasized the broader implications of the treaty violations, beyond just financial compensation. He said to The Guardian , “How many people might not have needlessly passed away if they had proper healthcare? If they had proper homes to live in, clean water, access to medicines?”

“It’s not just about the annuity. It’s about the erosion of our rights, the erosion of our people’s ability to live their lives.”

The Indian Act’s Lasting Inequalities

The Indian Act’s policies have perpetuated deep inequalities, affecting daily life on reserves.

The Guardian reveals that Chief Hardy points out the profound impact of the “deeply racist” policies under the Indian Act, describing them as deeply ingrained and pervasive in the daily lives of Indigenous communities.

The Deep Connection Between First Nations and Their Land

The First Nations’ profound connection to their land has been crucial for their survival, especially in the challenging Canadian climate.

Their traditional knowledge about land and water, essential for living a good life, or mino-bimaadiziwin, was compromised by the broken promises of the Crown. This loss has had lasting effects on their way of life, The Guardian reports.

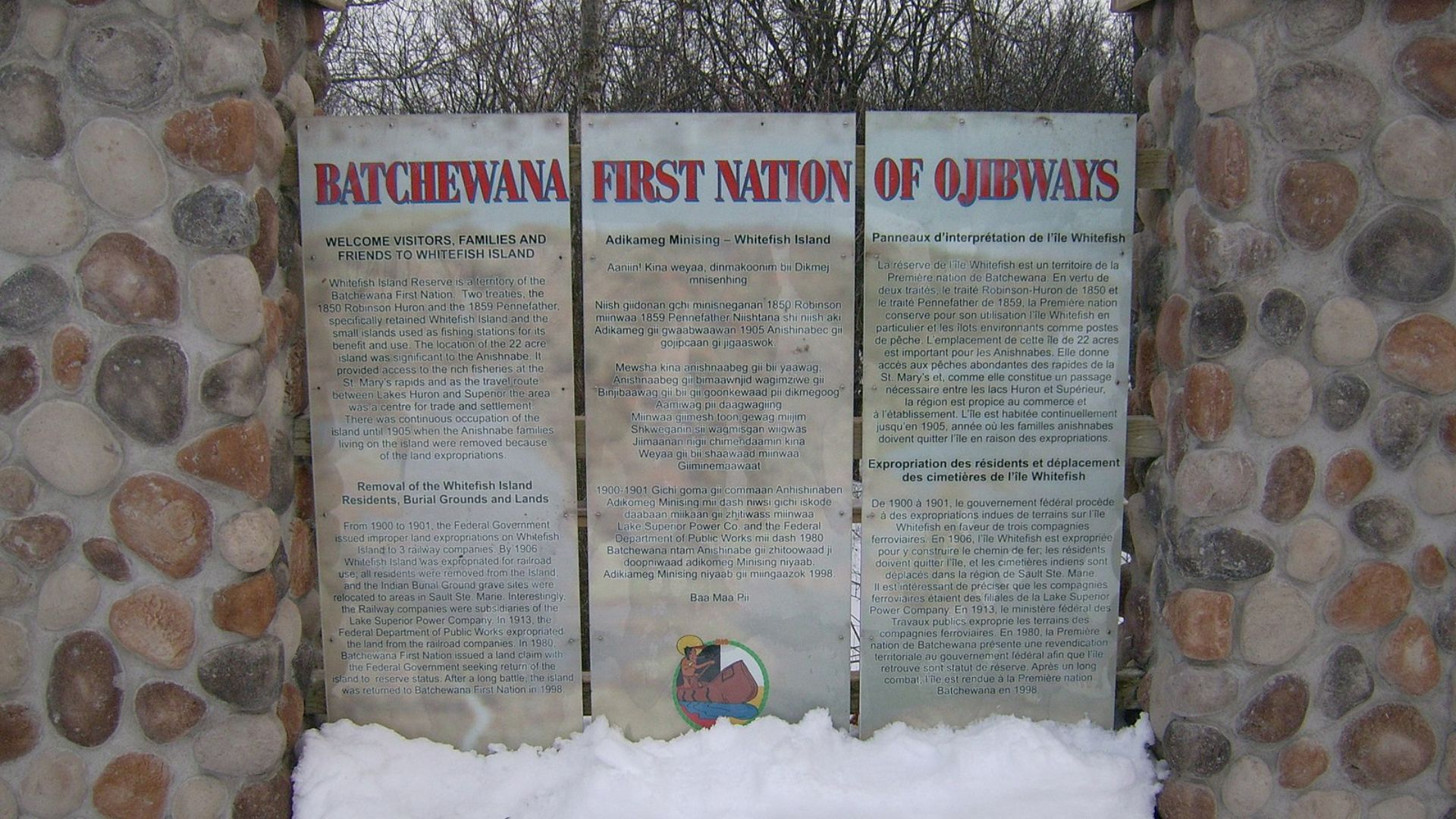

The Broken Promises of the Robinson Treaties

The Anishinaabe nations signed the Robinson Treaties in 1850, covering over 35,700 sq miles of land. These treaties included an augmentation clause for increased payments, which never materialized.

Over the following 173 years, the lands and waters encompassed in the deal generated great profits for companies – and large amounts of money for the province of Ontario, but the annuities remained capped at $4 per person and never increased, The Guardian reports.

Court Judge Plans to Uphold Treaty

Supreme Court Justice Patricia Hennessey agreed with the case brought before her by the First Nations groups in 2018.

She agreed the Crown dependencies had “completely forgotten” their original promise and argued the court possesses the “authority and the imperative” to seek restitution for the First Nations.

Justice Patricia Hennessy’s Understanding

Justice Hennessy’s ruling was notable for her effort to understand the Anishinaabe perspective.

Hennessy wrote, “They were giving the greatest gift of all – ‘the land and water over which countless generations of their ancestors had presided … the source of bimaadiziwin, which is to say, life in the fullest sense of the term.’”

$90 Billion Payday for These Groups

According to Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel-prize-winning economist, the Indigenous peoples could be owed over $90 billion.

“If you’ve owed somebody something year after year after year for 170 years, it’s a lot of money,” he told The Washington Post.

Canadian Government Disagree with Estimate

The government of Canada has argued it shouldn’t pay any more than $1.8 billion to the beneficiaries as they lost billions in developing the surrounding First Nations land.

However, Harley Schachter, co-counsel of numerous First Nations, argued against their opinion, stating, “After 173 years of government neglect and inattention, it is only fair and just for the chickens to come home to roost.”

The Future Potential of a Significant Settlement

The prospect of a significant settlement is seen as an opportunity to address urgent community needs.

The Guardian reports Chief Wilfred King of Gull Bay envisions the potential for substantial development, including housing, medical facilities, and infrastructure.

The Promise of Community Development

Chief King envisions using potential settlement funds for critical community development.

He said to The Guardian, “We were put in abject poverty. And now we’re coming to a possible resolution where our people will no longer live in squalor. They’ll be able to reach their full potential as First Nations people on the territory that was rightfully ours.”

Help For Future Generations

The possibility of substantial compensation has led community leaders to reimagine the future for their people. For instance, in the community of Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, sustainable development director Juanita Starr contemplates how the potential funds could transform their community.

She considers the impact on future generations, questioning to The Guardian, “How do we manage it for their futures to make sure they’re set up, like if my son wants to go to Harvard Law School or Trinity College?”

Indigenous Groups Hoped or Better

Kaitlyn Lewis, who works for some of the beneficiaries in the case, says, “The Indigenous groups thought they were negotiating a deal, or did negotiate a deal, that would bring in the good life for the community and for generations to come.”

She continued that the treaty “wasn’t sort of living in squalor” while settlers lived “lives of plenty.”